We use cookies to improve your experience.

Learn more.

By Tricia Arculus

Unfortunately, 10% of women and 8.4-25% of men (7, 10) suffer from Chronic Pelvic pain Syndrome. If you are one of them, you know how debilitating and far-reaching the effects can be. It can affect every aspect of your life from simple exercise and walking, to sleeping, leisure time, chores, work, sex, ability to concentrate, socialise as well as undermining the integrity of personal relationships, quality of life and both mental and emotional well -being.

If you have been struggling with CPPS for a while, you’ll have found that treatments for Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome are extremely subjective depending on your condition, triggers and the extend of your CPPS. Fortunately, there are some different path that you can follow to treat CPPS, all of which have offered hope to a number of people suffering. You don’t just have to live with Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome.

Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome, or CPPS manifests as pain or discomfort in the abdomen or pelvis, from the belly button to the mid-thigh, and lasts more than 6-months. This pain can be relenting and exhausting (2, 6) making it hard to carry on with day-to-day life.

CPPS isn’t triggered or caused by any proven infection or other obvious local pathology. In fact, the symptoms and triggers can be extremely variable in how they manifest. To make things trickier, presentation of CPPS often overlap with other urological disorders; lower urinary tract dysfunction; or sexual, bowel, and gynaecological dysfunction (1, 3). Lots of patients also experience CPPS alongside negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual or emotional responses. Each person is likely to experience different symptoms and they can fluctuate too, making it both a mentally and physically challenging syndrome.

Triggers for Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome are unclear, especially since the pain can be influenced by a range of different factors. For example, CPPS could be triggered by the joints and bones of your lower back and the pelvis; the muscles surrounding and affecting your pelvis; the nerves that enervate and travel through that region. It could have a gynaecological cause, be triggered through the prostate, or a neurological disease. But stress, anxiety and emotional factors can also be a source as can previous traumas caused by abuse or a simple smear test. However, the actual cause and pathophysiology remains largely unknown (10).

Studies suggest that chronic pain conditions, particularly fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) share several demographic, clinical and psychosocial aspects as well as pain-related features with CPPS – possibly reflecting shared primary pathophysiology (8). Temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction, postural anomalies, asymmetry of body and muscular disorders contribute to the long-term development of severe pain syndrome that can also reflect in the urogenital area (4).

The good news is that researchers have worked on a number of different ways to manage and treat Chronic Pelvic Pain. Different methods work for different people, and not every single option with work for every person. So far, there’s no single treatment that’s beneficial to all CPPS patients (5), but there is evidence, for example, that shows that psychotherapy can have clear benefits in CPPS management (9). You’ll need to approach each treatment with an open-mind and all the information that you can.

The key factors to establish before starting a treatment plan are actually relatively straightforward. It is essential to have a good understanding of the patients specific situation so that the optimal treatments can be applied to their situation (10). This helps to tackle the different CPPS causative factors and derived symptoms that invariably differ from person to person. With this information in mind, a professional will help the patient to establish a multimodal, therapeutic, individual approach to treating CPPS.

Currently, the advise is to treat and view CPPS as a set of associated symptoms rather than an entity of diseases (10). Clinical practices are offering a range of different approaches, including a plethora of medications, surgery, phytotherapies, hormones, pain control, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, acupuncture, TENS, psychotherapy, and physiotherapy.

The role of the physiotherapist would be to thoroughly assess all factors that might be exacerbating, contributing to and perpetuating the pain. Then, layer-by-layer they will help the patients to work through them.

Physiotherapy techniques including education, mobilisation and stretching out tight/overactive tissues and nerves, breathing techniques to aid relaxation, stress reduction and reduction of high tone, desensitisation of any hypersensitive muscles/tissues, down training of the pelvic floor muscles, biofeedback, pain modulation, advice re local skin irritation, fluids, bowel and bladder management, emotional support, myofascial trigger point release and relaxation techniques.

All of these have been applied successfully, and provide the patient with safe and effective tools for self-care and empowerment. If necessary other modalities may be used including Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) and frequency specific micro current (FSM).

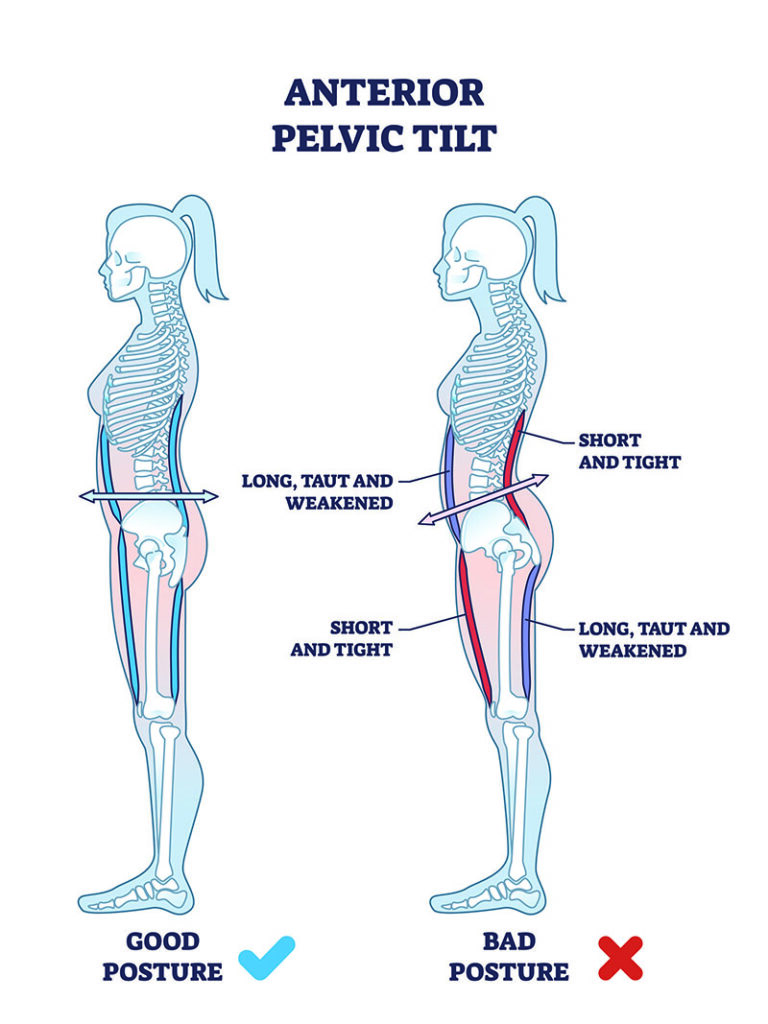

We would check that the pelvic joints and the joints of the surrounding areas that influence the pelvis, like the lumbar spine, hips, knees and ankle are aligned and functioning well.

The surrounding muscles will be assessed to see if they are strong enough to support the pelvis and surrounding joints or if they are too weak or too tight. A tight muscle is often a weak muscle that has to work too hard. Similarly, weak core muscle can lead to a hypertonic/tight pelvic floor as it takes over the function of holding the pelvis together.

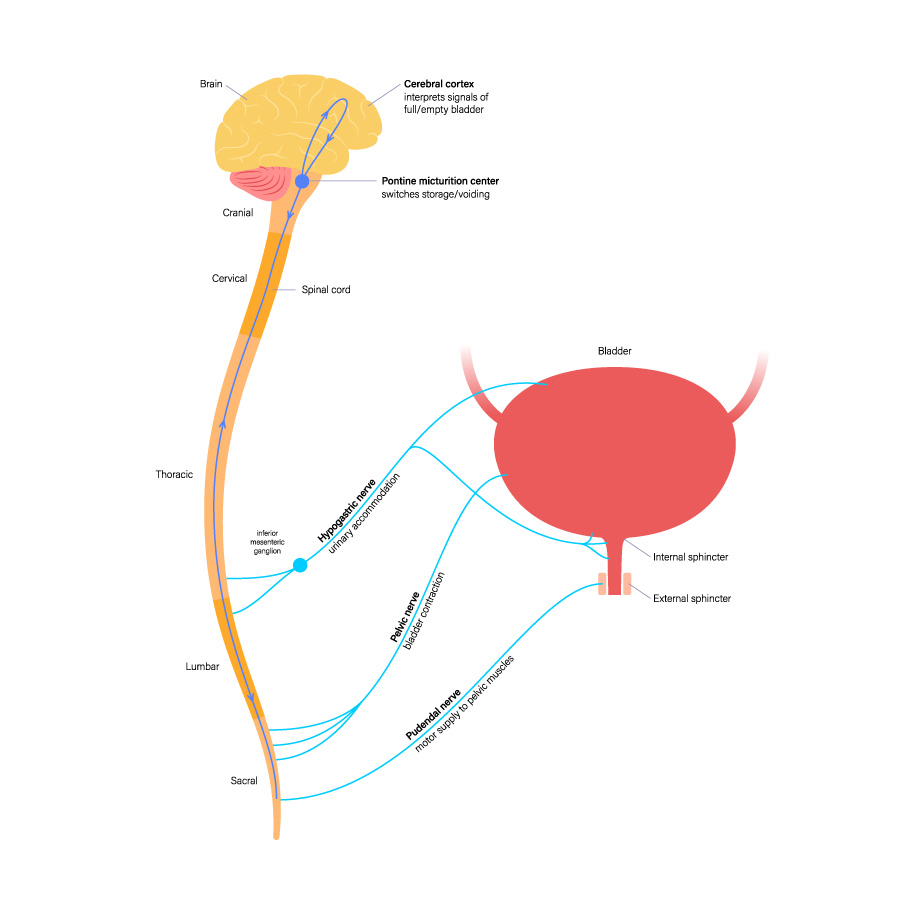

A common problem is often around the pudendal nerve. This can be injured through some of the causes mentioned above or it could just be that there has been too much pressure from repetitive loading of your pelvic floor.

In practice, this looks like too heavy weightlifting, cycling, fencing, ongoing constipation, really bad posture with prolonged sitting or from a hypertonic pelvic floor.

These things can improve with adjusting your posture and improving your core strength so you can maintain a good posture. Having a stronger core also allows the pelvic floor to relax better, which will take the pressure off the pudendal nerve.

A pelvic health physiotherapist will assess the pelvic floor through an internal examination through the vagina or the rectum. This gives a good indication of the strength of the pelvic floor and if it is too tight and impinging the pudendal nerve, which will trigger pain and hypersensitivity.

If the pelvic floor is too tight, we will manually work on it with trigger point techniques, myofascial release techniques and gentle manual stretching of the muscle. We also provide instruction on things to do at home, like stretching exercises of the surrounding muscles that will help the pelvic floor relax through fascial connections and muscle chain reactions.

We may teach breathing and other relaxation techniques that will help to reduce the muscle tension. We will also focus on desensitisation which will help reduce increased sensitivity in the area and consider tools like dilators or wands that might useful too.

These can be a contributing factor. They can be caused by surgery, endometriosis, infections and inflammatory processes. We have found that a combination of deep myofascial release techniques in combination with FSM (https://sutherlandhouse.life/frequency-specific-microcurrent/) can make a tremendous difference to this. FSM also helps well to reduce the inflammation that endometriosis triggers.

Written by Tricia Arculus

Registered and Chartered Physiotherapist

BSc (Hons) HCPC MCSP POGP PG Dip (Women’s Health)

FSM Practitioner

Acupuncturist

To book an appointment with Tricia, call

1. Baranowski A, Abrams P, Berger R, Buffington T, Collett B, Emanuel F, Hanno P, Howard F, Hughes J, Nickel C, Nordling J, Tripp D, Vincent K, Wesselmann U, de C Williams AC. IASP Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised). Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2011

2. Cheah PY,,LIiong ML ,Yuen KH et al. (2006) Reliability and validity of the National Institutues of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptoms index in Malaysian population. World J Urol. 23 79-89.

3. Engeler D, Baranowski AP, Borovicka J, Dinis-Oliveira P, Elneil S, Hughes J, Messelink EJ, de C Williams AC. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain 2016.

4. Korszun A, Papadopoulos E, Demitrack M et al (1998). The relationship between temporomandibular disorders and stress-associated syndromes. Oral Surg oral med pathol Radiol Endo. 1998, 86, (4) 416-420.

5. Magistro G, Wagenlehner F.M., Grabe M at al. (2016 )Contemporary Management of of CP/CPPS. European Urology, 69 (2), , 286-29

6. Murphy AB et al, 2009 Chronic Prostatis: management strategies. Drugs 2009; 69: 71-84

7. Pirola GM, Verdacchi T, Rosadi S, Annino F & De Angleis M ((2019).Chronic prostatitis: current treatments. Res Rep Urol. 2019. 11 165-174

8. Rodrigues MA, AFariN , Buchwald (2009)NI of diabetes and digestive and Kidney diseases working group on urological CPP. Evidence for te overlap between urological and nonurological unexplained clinical conditions. J Urol, 2009; 182 (5)2123-2131.

9. Sung, Y. H., Jung, J.H., Ryang, S. H., Kim, S. J. & Kim, K. J. (2014). Clinical significance of N.I.H. classification in patients with CP/CPPS. Korean Journal of Urology, 55 (4), 276 – 280.

10. Zhang J, Liang C, Shang X, Li H. Am (2020) Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Disease or Symptom? Current Perspectives on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. J Mens Health. 2020 Jan-Feb;14(1).